BWTA Presentation c. 1900: The Life and Work of Father Theobald Mathew – ‘The Apostle of Temperance’ 1790 – 1856

‘Ladies and Gentleman,

We purpose giving you this evening a short account of the life and work of the Rev. Father Theobald Mathew, popularly known as ‘The Apostle of Temperance.’ The Reformation caused by Father Mathew in the habits of his countrymen and women was, and still is a source of wonder to all thinking people, and we trust that this short description of his great Temperance Crusade, will arouse new hopes in the hearts of some present day workers in the cause – a cause which if triumphant, would create more happiness, virtue and prosperity in our land, than the removal of any other disability.

Theobald Mathew was born on the 10th October 1790, at Thomastown Castle, Tipperary, a fine old mansion, the residence of his kinsman George Mathew, afterwards Earl of Llandaff. The boy was one of the younger members of a large family; his parents were devout Catholics, and his Mother greatly longed to see one of her sons enter the priesthood. One day sitting at dinner, she looked round at her children sighed, and said “Is it not a pity? I have nine sons, and not one of them to be a priest!” The elder boys who had disappointed her by showing no inclination to enter the career, she thought the highest service they could render, hung their heads and were silent, but little Theobald, who was still quite a child, started up, and running to his Mother took her hand exclaiming, “Don’t be uneasy Mother! I’ll be a priest!” It was only a childish impulse to please the Mother he so dearly loved, but from that moment all the family looked on the boy as already devoted to the priesthood, and his influence over his brothers was doubled. Theobald was from his earliest childhood distinguished by a very loving and lovable disposition, utterly unselfish, always delighted to help the poor people, who often came to his Mother’s door, and to aid her in her charities to the blind and crippled among them.

His boyhood was passed in one of the loveliest parts of Ireland, and in visiting his relatives, often saw some of the most famous relics of Ireland’s ancient glories, such as this picture of Holycross Abbey shows us. The stories he would hear of the old Abbey and its associations, would no doubt tend to deepen his childish resolve to be a priest. Whilst the impressions made on his mind by such beautiful spots as this, the Tore Waterfall at Killarney, would foster in him, that deep love of his country which was ever after so prominent amongst his characteristics. After receiving his earliest lessons from his Mother, Theobald Mathew was sent to school in Killkenny, and here again there was much in the city and its surroundings to deepen his love of Ireland.

School days being over, and his early impulse towards the priesthood having ripened with the years, Theobald Mathew entered Maynooth, the training college, where most young Irishmen studied for the Roman Catholic ministry. His college days were passed in strict seclusion, and were full of hard work. Not content with the training given at Maynooth, the young student afterwards spent some time at Trinity College, Dublin, to fit himself more completely for the life he had chosen. On being ordained, he at once joined the poorest and most humble of the orders of friars then in Ireland – the Capuchins, and was appointed to work in Kilkenny, where he had been at school.

The church of the Capuchins was a very small, poor, and insignificant place, and the friars living rooms were so ill-ventilated, damp and unhealthy that they suffered a good deal from their surroundings. Even while preaching and working at such a small church, however, Father Mathew soon attracted public attention; he had a clear, beautiful voice and a winning manner, and the people quickly found out that he was always sympathetic and ever ready to do anything in his power to help those who were in trouble or destitution. While he was at college too, he had taken great pains to make himself perfect in speaking the old Irish language, in order that he might be better able to talk with the country people, many of whom at that time knew no English. This he found a great help in winning their confidence, for not all the priests could speak Irish, and Father Mathew was soon the best beloved minister among the poorest classes of the city. During the few years he stayed in Kilkenny, he suffered several family bereavements, that which fell most heavily on his loving heart being the death of his youngest brother Richard. This lad was considerably his junior, and had come to live with him for his education – a bright, vigorous, promising boy, whose early death was a stunning blow to Father Mathew, and made him ever after a little more tender than he had been towards all in sorrow.

A little later the good priest was appointed to work in the city of Cork, and here the greater part of his life was spent. Cork was then a very dirty, rather over-crowded place, many of the people were of drunken habits, and there was a large proportion of pauperism and crime. Father Mathew made the visitation of the Hospitals, the Jail, and the House of Industry (the Workhouse of that time) a regular part of his work, and soon became very well known in the city. In the year 1832 there came a time of awful trial to Cork – an epidemic of Cholera broke out, and in a very short time Death was gathering his harvest in every street, claiming victims in almost every house. We may well be thankful that we do not know now-a-days, what a visitation of what terrible plague means. All the priests devoted themselves to tending themselves to tending the stricken people, ministering to the dying, helping the widows and orphans, showing them how to disinfect their homes, but amongst them all Father Mathew was ever foremost; he seemed to do the work of three men, and in that awful time of death and panic he kept always calm and ready, never weary of his many sad duties, and seeming to bear a charmed life. When at length the epidemic had spent itself, the people of Cork loved Father Mathew more than ever, and would have done almost anything for him. Being appointed one of the Governors of the Workhouse, the priest became acquainted with another Governor, William Martin, a prominent member of the Society of Friends; this good man, whose heart was as kind as his face was grim, had been trying for years to start a Temperance Society in Cork, but with no success owing to the fact that the people were unwilling to listen to a Protestant, the great majority of them being Catholics. This it happened that William Martin and his two chief helpers, Richard Dowden and Nicholas Dunscombe, both Protestant ministers, were very anxious to get Father Mathew to take up the Temperance work, for they knew the people would listen to him. Whenever any case of destitution due to drink came before the Governors of the Workhouse, William Martin would turn to his friend and say, “Oh, Theobald Mathew! If thou would’st but take this work in hand, much good might be done for these poor creatures!” Again and again that appeal sounded in the priest’s ears, “Oh Theobald Mathew! drink has done this! if only thou would’st take the lead, much good might be done in this city!”.

Father Mathew, though always very abstemious, had not been brought up as an abstainer, he had already almost more work than he could do, and many of the distillers and publicans of the city were amongst the largest subscribers to his orphanages and other charities; several members of his own family were engaged in the liquor traffic, and it was no easy matter for him to take up a work which seemed certain to ruin his popularity, besides risking the withdrawal of many subscriptions from his charities. He was then in his 47th year, at an age when few men readily undertake new work, and we cannot wonder that he hesitated. Total Abstinence was then an almost unheard of thing, its few advocates were looked upon as being unreasonable fanatics, and of course they had not then the splendid scientific evidence in its favour that we have today. But Father Mathew’s heart was touched, not only by his friend’s appeal, but by the sad cases he could not help seeing in the Hospital, in the Jail, as well as in the miserable homes of many of his people; he gave the question much thought, long he prayed to God for guidance – then one day William Martin’s heart was gladdened by a message that Father Mathew wished to see him, and on going round to the priests house in Cove Street , the good old Quaker rejoiced to hear his friend say “Well , Friend Martin, I have decided; I will take up the work of the Temperance Society, and we will hold the next meeting in my schoolroom”.

That meeting held on the 10th April 1838, was a very notable gathering. William Martin spoke, so did Richard Dowden and Nicholas Dunscombe, but the speech of the evening was Father Mathew’s. Very simply he told the people how he had been led to take this step, very earnestly he appealed to them to join in fighting the curse that had ruined so many homes in the city, and then holding up his left hand, he repeated the words of the pledge and saying “Here goes, in the name of God!” he signed the pledge book. Eagerly many of his flock followed his example, and sixty names were added to the Temperance Roll that night. Other meetings followed: they were held out of doors all that summer, and in the largest buildings available during the next winter – from all the countryside round people came into Cork to hear Father Mathew and take the pledge, until by January 1839, there were over 200,000 names on the roll. Such enthusiasm had never been known in Ireland over any religious or social movement – William Martin’s expectations were far outdone, Father Mathew himself was amazed – and still the wave of Temperance rolled on. The cause made such progress and was the means of so much evident improvement in the condition of the working classes particularly that many had who formerly scorned the ‘Temperance fanatics” rallied to Father Mathew’s side. School masters declared that the children came to school more regularly, and were better fed and clothed, and more fit to learn, as a consequence of the change in their parents’ drinking habits; employers of labour said their men were more reliable and less quarrelsome, the police found they had not nearly so many arrests to make, and all classes joined in praising the Temperance Crusade. Even some of the distillers admitted to Father Mathew that though their trade was diminishing and their profit grew less and less, they were glad to see how much improvement had been made by his efforts, and a number of them gave up business, and went into other lines of trade. Father Mathew at this time rose at 5am and only retired late at night, in order to cope with the constant work of the Crusade as well as his priestly duties, and it is said that his room often bore a worse smell of liquor than even a public house, for it was thronged day and night by penitent drunkards, and no matter how filthy and degraded they were, Father Mathew would always see them and by kindness and encouraging words, endeavour to put fresh hope into their hearts as he gave them the pledge.

Invitations from all parts of Ireland now began to pour in, and in December 1839, when the work was well established in Cork, the “Apostle of Temperance” visited Limerick. Even on the day before his arrival, the roads leading to Limerick were thronged with people eager to see, hear and take the pledge from one whom they regarded with feelings of profound reverence and enthusiasm. The difficulty of feeding and housing such a multitude was enormous, but private individuals did their best, and all the public rooms were thrown open by the civic authorities. So great was the rush of people that the iron railings opposite the house where Father Mathew was staying were thrown down, and more than 20 people fell into the river Shannon, which flows through the city. Happily no lives were lost, for the troops had been called to help keep order, and the mounted men were able to rescue those who had fallen into the river. In four days of strenuous toil, in meetings and interviews, 150,000 names were added to the Temperance Roll. From Limerick Father Mathew went to Galway, passing Castle Connell where there are beautiful rapids of the Shannon, and here also he had great success. After a brief time in the wilds of Connemara, he returned to Cork and shortly afterwards visited Waterford, where he had a wonderful Mission, adding about 80,000 recruits to his Temperance Army. The year before the Crusade began, the Judges at the Waterford Assizes had 55 cases before them, many of the prisoners being charged with murder or attempted murder; two years later, when the work of Temperance was triumphing, there were but five prisoners at the Waterford Assizes, and Judges and Police alike pronounced the improvement to be due to the great reduction in the consumption of whiskey, which had gone down to one quarter of the amount used two years before.

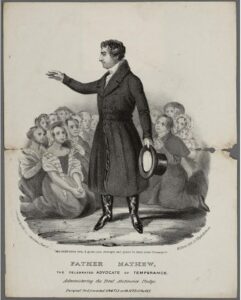

It was very difficult after such a lapse of time, to get any satisfactory pictures of Father Mathew’s meetings, but you may like to see this (image – replacement used as glass slide has not survived), showing the beloved leader giving an address to a country audience; I greatly doubt whether Father Mathew ever stood right on the edge of the platform, holding his hat so that it could not fail to be very much in his way, but though the accuracy of this picture might be doubtful, there is no doubt at all as to the people’s eagerness to hear him – their faces show that clearly. In such audiences there were many who could not read or write, so when he had finished speaking Father Mathew used to ask all who wished to take the pledge to kneel down, then they repeated the words after him, and the good priest would go among them speaking kindly words of advice and cheer to each; his helpers then took the names and gave the people their cards.

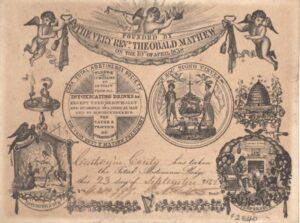

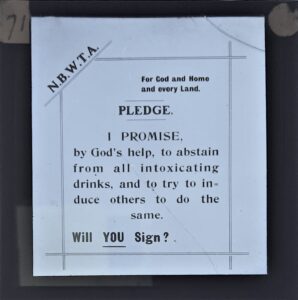

(On this Pledge Card) the cross on one of the medallions is clear, and reminds us that in this wonderful Crusade, Temperance was always linked with religion – Father Mathew’s appeals were made on the highest possible ground. The writer of this lecture knows one such card, carefully preserved by a friend in London, dated 1843, and bearing a number above 2,000,000! It is hard to realise how such an enormous number of pledges could be gained in so short a time by the influence of one man.

In that delightful book on the scenery and characteristics of Ireland, by Mr and Mrs S.C. Hall, when giving an account of their travels in the country in 1840, they say with reference to the Temperance Crusade, “Previously to our latest visit to Ireland, we had entertained strong doubts, first as to the extent of the reformation, next as the likelihood of its durability. As in our case these doubts have been dispelled, it our duty to labour to remove them from the minds of those of our readers by whom they may be still entertained. In reference to the extent to which sobriety has spread, it will be almost sufficient to state that during our recent stay in Ireland, from the 10th of June to the 6th of September 1840, we saw but six persons intoxicated, and for the first 30 days we did not encounter one. In the course of that month we had travelled from Cork to Killarney, round the coast; returning by the inland route, not along mail-coach roads, but on a jaunting-car, through byways as well as highways; visiting small villages and populous towns; driving through fairs; attending wakes and funerals, returning from one which, between Glengariff and Kenmare, at nightfall, we met atleast a hundred substantial farmers, mounted – in short, wherever crowds were assembled and we considered it likely we might gather information as to the state of the country and the character of people. We repeat, we did not meet a single individual who appeared to have tasted spirits; and we do not hesitate to express our conviction that two years ago, in the same places and during the same time, we should have seen many thousands of drunken men. From first to last, we employed about fifty car-drivers; we never found one to accept a drink; the boatmen at Killarney, proverbial for drunkenness, insubordination, and recklessness of life, declined the whiskey we had taken with us for the bugle-player, who was not ‘pledged’, and after hours of hard labour they dipped a can into the lake and refreshed themselves from its waters. It was amusing, as well as gratifying to hear their new reading of the famous address to the echo ‘Paddy Blake, plas yer honour, the gintleman promises ye some coffee when ye get home!’ (this always used to be whiskey in old times). On the Blackwater, our boats’ crew put ashore to visit a clear spring with which they were familiar. The whiskey-shops are closed or converted into coffee-houses; the distilleries have, for the most part, ceased to work; and the breweries are barely able to maintain a trade sufficient to prevent entire stoppage. Of the extent of the change, therefore, we have had ample experience; and it is borne out by so many who live in the towns as well as in the country, that we can have no hesitation in describing sobriety as almost universal in Ireland.”

Mrs S.C. Hall also tells this story of one of the boatmen, before and after he came under Father Mathew’s influence. He was a very fine looking man, over six feet, his skill as an angler was so great and so generally esteemed that he was sure of constant employment and could easily earn enough to give his family every comfort, yet when two gentlemen, wishing to engage him, went to talk to the man, they found him half-drunk and so ragged that they gave him a new suit of clothes to make him fit to go with them the next day. He pawned the clothes, and when the gentlemen went to look him up they found him drunk again, his wife stretched on the floor of the miserable cabin, insensible, the children cowering, crying, on a heap of damp straw in the corner, their only bed; no food in the house. A few days later, going again, they found the man had been taken to jail, having in a fit of drunkenness, terribly beaten his wife, who was also drunk at the time, and had bitten his hand so badly as to maim it. Leaving the district they saw no more of him but twelve months afterwards heard that he had joined the Temperance ranks under Father Mathew, and had entirely reformed, and his wife with him; that the children were now well clad and well fed, the dirty miserable cottage was now clean, comfortable, and properly furnished, while the man visits the savings-bank as often as he used to visit the pawn-office. Of their relapse into the former degradation and misery there seemed no danger at all.

It was a very happy thing that Father Mathew’s Crusade was the means of bringing beauty into human lives which had been sorely lacking in the beauty of right living, though set in the midst of such lovely surroundings.

Father Mathew’s visit to Dublin brought him one of his greatest successes, he had huge open air-meetings, one of them held outside the Custom House, and a specially interesting gathering was held in the Royal Exchange in order to give the ladies of the city an opportunity of hearing him without the risk of making their way through the great crowds. At the special meetings 400 ladies of rank and fashion signed the pledge, a splendid gain, for many of them were the mothers of sons who were likely to influence public life in Ireland.

(This image) showing the fine statue of Daniel O’Connell which the Dublin people are so proud of, reminds us that O’Connell himself became one of Father Mathew’s followers; he was at that time the popular leader of the country, named the ‘Liberator’ by his enthusiastic Irishmen, and often engaged in political agitation in which his followers needed careful leading if violence was to be avoided. He saw what a safeguard Temperance would be to his men, and very wisely set them as a good example by going to one of Father Mathew’s meetings and there taking the pledge. O’Connell was Lord Mayor of Dublin that year, and his action brought in thousands more to join the Temperance cause. He was ever after a firm friend to Father Mathew, who several times visited him at Derrynane House – this fine mansion was a gift to Daniel O’Connell from the Irish Nation, as a mark of the love they bore him because of his gallant and wide efforts to remove many of their disabilities. Leaving Dublin, Father Mathew went to the town where long before he had been at College – Maynooth – and during his short stay he was the honoured guest of the Earl of Leinster, at his mansion Carton. Not only amongst the townspeople of Maynooth, but in the college itself, large numbers took the pledge, and the ‘Apostle of Temperance’ especially rejoiced over the 250 students and more than 20 professors who joined in his Society, for these young priests would be sure to have strong influence in their parishes in days to come.

Going on further North, a brief visit was paid to Londonderry, the city of such stirring tales of old war-times; here too a glorious success crowned Father Mathew’s efforts, and his flagging strength was renewed by the joy he felt as much as by the splendid bracing air of this grand coast. Wherever he held a Mission, local Temperance Societies were formed, and whenever it was possible a Reading Room was opened, that the new converts to the cause might carry on the work when Father Mathew had departed, and have a social centre too, instead of the Public House from which many of them had been won. Even in remote country districts, where often the people’s homes were not much better than these cabins, the little Reading Rooms proved centres of light and usefulness, and the meetings held in them were the training-grounds for many eloquent young speakers, some of whom afterwards did good work in America. When he had travelled nearly all over Ireland, Father Mathew at last consented to accept the often repeated invitations he had received, and spend a little time in Scotland – we need only to say that his success there, especially in Glasgow with its large Irish population, was very great, and did much to put on a firm footing the Temperance Societies already started in that part of the kingdom.

Returning to Ireland, Father Mathew was royally welcomed home by his people in Cork, and found the cause had suffered little by his constant absences from the city. His friends had some very striking statistics to show him….they give clear evidence of the close connection there is between drink and crime, and it is easily seen how much the Temperance Crusade saved Ireland even in mere money expenditure on prisons and police. Very soon after his visit to Scotland the English Temperance leaders begged Father Mathew to come and give them a helping hand, and he willingly answered the call, though his health was far from satisfactory just then; he spoke in many of the largest towns such as Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield, besides paying flying visits to many smaller places. In London the newly started Temperance League got up a grand procession in Hyde Park, and there Father Mathew addressed an enormous crowd, amidst every great demonstrations of enthusiasm. This visit of Father Mathew’s bore abundant fruit not only at the time but in after years, for it was the means of starting a great Roman Catholic Society, the League of the Cross, which has ever since been a powerful influence for good amongst the Irish in London, Liverpool, and other parts of the country. In Norwich Father Mathew had particularly happy meetings, the clergy and ministers of all denominations joining to welcome him, and taking part in great public gatherings at which he spoke – I am afraid Norwich has lost some of her early enthusiasm for the cause, though there are some very fine temperance workers in the city.

Soon after his return to Ireland, Father Mathew’s heart became very anxious about his beloved country, for the famine was already darkening some parts of the land. The potato crop failed entirely in 1846 and 1847, and we can hardly imagine, in these days of plentiful supplies of food from all over the world, what a terrible thing such a failure was then. It was well-nigh impossible to feed a starving nation from the outside then, and though many noble men and women, in Ireland and in England strained every nerve to cope with the emergency, it was almost in vain; fever followed hard on the famine; the dreadful ‘Black Typhus’, and the poor people died by tons of thousands, dropping dead for lack of food , or dying alone in their deserted cabins too weak from fever to call for help.

Father Mathew worked like ten men, starting soup kitchens, organising bands of helpers, gathering in food and money from his many friends in England and America. But it was almost in vain, and when the time of terror had passed, he was a worn out, broken-hearted man; his little local Temperance Societies were in most parts of the country broken up, many of the members had died in the Famine, the Reading Rooms were closed and those of the young workers who survived soon turned their faces to the West; very many of them emigrating to the United States to seek there the means of livelihood which their own stricken country could not give them. And so it seemed that Father Mathew’s splendid work would bear very small harvest in the end, for many of the older people when the famine was over, went back to their old drinking ways in their sorrow, and the Government blindly went on granting new licences wherever they applied for, so that gradually the Liquor Traffic regained much of its lost power, and Ireland was again brought under its evil sway. Father Mathew was strongly urged to go to America to recover his health if possible, and although he had one stroke of paralysis, he regained strength sufficiently to undertake the voyage, and even on the ship did a good share of temperance work taking many pledges from the Irish emigrants on board. So earnest was his desire that none of his friends should suffer through his weakness, that before the sailing, he went specially to Dublin to speak for his friend Charles Gavan Duffy, who was at that time out of favour with the Government owing to his political actions. In America Father Mathew visited the hot springs of Arkansas, which did him little good, and then took a prolonged rest in the South. I do not know whether Father Mathew ever met Neal Dow during his stay in the United States, but that fine young worker even at that early date a prominent man in the American Temperance ranks, and afterwards famous as the Governor of Portland who first enforced the Prohibition Law, must certainly have heard a great deal about the ‘Apostle of Temperance’ and no doubt felt the inspiration of his noble self-sacrificing life.

Father Mathew was splendidly received in many of the American cities he visited, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Mobile, New Orleans, and Washington amongst them. This picture shows us the Capitol in Washington, where the American Parliament meets. As soon as Father Mathew’s arrival was known to the members of the Congress, they passed a resolution admitting him to the floor of the House, and when he entered to take the seat so courteously offered him, the members all rose to receive him. The Senate also welcomed him in similar fashion, thus conferring on the humble Irish priest the highest honour which could be shown towards any subject of another country by the representatives of that great Republic. The following evening Father Mathew was entertained by the President of the United States, who invited fifty of the foremost men of the country to meet him, and gave him many valuable introductions. The banquet was served in sumptuous style, but though the choicest wines of Europe appeared on the table, scarcely any wine was used by the company, and none by the host, out of respect to the guest of the evening.

After many months of travelling and work in America, during which he met many old friends and made many new ones, Father Mathew returned to Ireland in December 1851. The people of Cork gave him a right royal welcome, holding a special Grand Parade of all the Temperance Societies in his honour , but they noticed sadly that he was little, if any, the better for his travels. By this time the Temperance work had begun to rally a good deal after the terrible check it had received owing to the famine, but it never recovered full power, and Father Mathew was no longer able to be the main-spring of the movement as of old. In 1854 Father Mathew went to Madeira for a time, but returned no stronger and from then until his death in December, 1856, he was only able to do very quiet work for the cause he loved so well and to which he had devoted so many strenuous years.

His closing days were spent at the house of his brother, Rothclogheen; he was surrounded by the loving care of his brother and his numerous nephews and nieces, and the last months were very peaceful and happy. In his very last days he was still eager to see any who came desiring to take the pledge; even when he could not speak such visitors were brough to his bed-side, they repeated the words of the pledge, and the dying priest would manage to make the sign of the Cross on their foreheads with his palsied hand and silently give them his blessing. On Friday 12th December 1856, the city of Cork poured out its’ population onto the streets to pay the last tribute of respect to the memory of its’ great citizen, and through the vast crowd of people the funeral cortege, extending nearly two miles in length, wound its way to the cemetery. Every class, every rank, every party, every creed, had its representatives in that sad procession, which was closed by the truest mourners of all, the very poorest folk, to whom the ‘Apostle of Temperance’ had ever been such a generous friend.

For many years after, occasionally even now, men would go to Father Mathew’s grave to pray, and to perhaps renew, the vow of total abstinence. Year by year, in Cork, a great Temperance meeting is held in the open air, around the statue erected in his memory, and in Dublin too, where, in Sackville Street, not far from the great monument to Daniel O’Connell, this simple memorial stands, the people gather round the statue of the humble Capuchin friar, and keep his memory green by carrying on the work he so much loved. Many Temperance Societies in Ireland are called by his name, and the wording of their Pledge Card, though intended for Roman Catholics, surely has a lesson in it for us also.

Within very recent years splendid Temperance work has been done by the ‘Catch-my-Pal’ movement, under the leadership of a Protestant minister, the Rev. R.J. Patterson.

I trust tonight’s brief glance at the life-work of Father Mathew, the fine old pioneer temperance Apostle of Ireland, and the fact that his work is still needed, and happily still nobly carried on will help to inspire afresh all those who are striving to fight our Empire’s battle against the insidious enemy, Alcohol, and may also help to bring into our ranks some new recruits, for they are greatly needed, and I would plead with the young men and women, lads and girls, here tonight, to come forward and join in this moral welfare, the sake of God, and Home, and Every Land.’