I can’t quite believe that we are already into December, yet here we are with Christmas on the horizon. I thought it might be interesting to take a jump backwards in time and have a look what was being reported during the month of December in some of the old periodicals in our archive.

With the candle industry booming – who doesn’t love the warm flickering glow of a candle, to make us feel all warm and cosy? – one article that jumped out was in the Woman’s Herald of 1892 entitled ‘Girls and Their Trades’ and gives a glimpse into the story of women and girls working in the Salvation Army’s ‘Darkest England Match Factory’.

The pre-electric or gas home would have been lit by candlelight or gas lamps, so matches were an indispensable commodity in enabling some sort of activity to continue during the dark days and nights of winter. Under the dim light of candles or a lamp you would have at least had some ability to sew, read and cook.

We had an electricity cut at home for a very short time one evening recently and we went on the hunt for candles and torches under darkness. The candlelight suddenly didn’t give me such a warm and cosy feeling anymore, it felt a lot more oppressive and depressing. It is difficult to imagine us living now without the luxury of electric lighting at just the flick of a switch. Imagine those low paid workers toiling away at home to make ends meet, working under those dim and gloomy conditions for hours on end when the darkness would have been creeping in so early on winter days.

The manufacture of matches was a booming industry and demand was high for the ‘Safety Match’ which was produced by the millions every day. It wasn’t just in the home in the 19th century that an easy and safe form of ignition was required; the Industrial Revolution had been in full swing with the expanding railways, factories, iron works and textile mills being powered by machinery requiring the initial spark of a flame.

The Industrial Revolution saw a huge increase in people moving into the cities for employment opportunities and with the need for cheap labour resulted in hazardous working conditions, poor pay and long hours. Gradually, legislation did come into force providing some protection for the workforce in particular around child labour, but there was also a need to ensure that these laws were enforced. The introduction of factory inspectors was an important development, beginning in the mills and eventually covering most workplaces.

Behind the Woman’s Herald article looking at the conditions of the girls working in the match factory, is the story of how The Salvation Army took up the plight of the match girls in the late 19th century with their poor working conditions and how they made improvements.

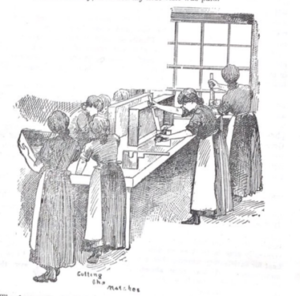

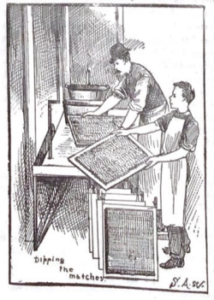

The match makers were mostly women and young girls, working up to 14 hour days, with low pay that was often reduced even further by fines that were incurred for lateness, untidiness, talking and going to the toilet. One of the most awful potentially fatal outcomes of working in one of these match factories though, was a condition known as ‘phossy jaw’.

The match making process included the use of toxic phosphorous which could decay the bone, causing terrible pain, disfigurement and possibly death if left untreated. These women and girls were already dealing with severe poverty and were just trying to make some sort of living. Necessity meant they also had to deal with these awful working conditions and the potential of contracting a life altering, if not life-threatening disease.

The conditions of these workers soon became public knowledge and in 1888 the match girls strike took place, when around 1500 workers marched out of the Bryant and May factory. They were one of many match manufacturers to use poisonous phosphorous in their production process. The plight of the match girls was also on the radar of the Salvation Army. The ‘Darkest England Scheme’ was the Salvation Army’s social work programme which aimed to combat amongst other things, poverty, hunger, and homelessness. ‘Sweating’ was the labour practice of long hours, low pay and high workload in both home working and factories and the sweated match makers soon became part of the Salvation Army’s campaign of improvement.

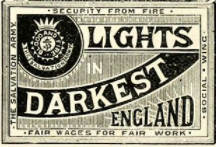

In 1891 the Salvation Army opened their own match factory in Lamprell Street, Old Ford in East London where harmless red phosphorus was used in the match making process with much improved working conditions and higher wages for the workforce. The matches were named ‘Lights in Darkest England’, following on from the book ‘In Darkest England and the Way Out’ written in 1890 by The Salvation Army Founder William Booth about social poverty and how this could be addressed. The matchbox advertised ‘Fair Wages for Fair Work’.

In 1891 the Salvation Army opened their own match factory in Lamprell Street, Old Ford in East London where harmless red phosphorus was used in the match making process with much improved working conditions and higher wages for the workforce. The matches were named ‘Lights in Darkest England’, following on from the book ‘In Darkest England and the Way Out’ written in 1890 by The Salvation Army Founder William Booth about social poverty and how this could be addressed. The matchbox advertised ‘Fair Wages for Fair Work’.

The author of the Woman’s Herald article had decided to visit the Salvation Army factory to see for herself the work connected with the ‘Social Scheme’ and how much better the working conditions were in this new factory. She found 150 workers were employed, of which 80% were women. For a nine hour day they were being paid 16 shillings per week. This exceeded the wages of workers at other match factories and in consequence they had many more applications for employment. Unfortunately many of these poor women and children were turned away, as demand for these particular matches was not high enough yet to employ a larger workforce.

The workers in this forward thinking factory were described as looking both happy and healthy but a vivid description was provided detailing the true horrors of phossy jaw. A woman gave an account of her own experience of phossy jaw contracted in her previous employment. She was now convalescing whilst working in the Salvation Army factory, free from the poisonous phosphorus that would almost certainly have killed her. She showed part of her face where the jaw had rotted away. ‘“The pain”, she said “was terrible. It was if a cylindrical file was grinding round and round slowly in the jawbone.” She had a family and husband, and when the pains, (which stop for a time, after a loss of a piece of bone, and then return) she had to leave her little ones and husband, and keep to a room by herself, so terrible was the odour of the matter running from the decayed part….’. This was a truly appalling condition; no wonder so many were trying to find employment in a factory promising a safer working environment.

The reality though, was that the Darkest England Matches were more expensive to produce than the competition and therefore, were more expensive to buy. Demand for these matches was not higher because of the price. Even with the campaign to urge the public to only buy these Salvation Army factory matches because they were not produced by ‘sweated’ workers and were produced safely, after 10 years of production the factory was closed. It could not compete with cheaper mass production. However, along with the strike of 1888, awareness had been raised and other factories were forced to improve their working conditions and pay.

The reality though, was that the Darkest England Matches were more expensive to produce than the competition and therefore, were more expensive to buy. Demand for these matches was not higher because of the price. Even with the campaign to urge the public to only buy these Salvation Army factory matches because they were not produced by ‘sweated’ workers and were produced safely, after 10 years of production the factory was closed. It could not compete with cheaper mass production. However, along with the strike of 1888, awareness had been raised and other factories were forced to improve their working conditions and pay.

By January 1900, a newspaper article reported that at a meeting of the shareholders of Bryant and May, they had announced ‘The End of “Phossy Jaw”’; the firm had ‘just acquired valuable patents, by which they would abolish altogether the use of white phosphorous in all their matches.’ Later in October of the same year an advert for Bryant and May matches stated that ‘Special Patent Safety Matches Contain No Phosphorous’. It took another eight years until 1908 for an Act of law prohibiting its use in matches.

When I strike a match to light a candle this Christmas, I will definitely give some thought to those women and girls trying to earn a crust in those match factories for their families; it was really not that long ago. I won’t be taking our modern health and safety at work for granted either.