Whilst cataloguing material in our archives, I came across correspondance from the 1920’s between the National British Womens Temperance Association (NBWTA – forerunner to the White Ribbon Association) and the London Temperance Hospital. I was keen to find out more about the history of this hospital and its connection with the NBWTA.

For hundreds of years alcohol was used in the medical profession to treat all sorts of ailments, both physical and psychological. During the nineteenth century this increased alongside the practice of promoting the idea that consuming certain drinks would have health benefits. At the end of the nineteenth century doctors began to debate the effectiveness of using alcohol as a form of medical treatment, and the moral implications of prescribing alcohol were highlighted by temperance campaigners.

It makes sense that the British Women’s Temperance Association, which was founded in 1876, would have taken a keen interest in the practices and outcomes of this temperance hospital. Taking a look back through our collection of periodicals I found articles highlighting the use of alcohol in medical practice, in the Associations monthly paper called the British Women’s Temperance Journal (BWTJ).

In the July edition of 1883, an article was published – ‘The Administration of Alcohol in Disease’. It discussed a paper written on the subject by Dr Richardson, which had been read before the Medical Temperance Association. One doctor expressed the prevailing ‘medical dogmatism’ of the time, regarding the prescribing of alcohol – ‘Again and again they had said to patients, “You will die if you do not take alcohol,” and again and again the living patient had shown the absurdity of the false prediction.’ It is hard to believe today, that such a practice existed and in the not too distant past.

Another quote from an article of the same year 1883 in the BWTJ, ‘Opinions Change’, gives us a clear understanding of how ingrained this form of treatment was, when Dr Hare, Physician to University College Hospital, is quoted as reminiscing “I well remember the time,” he said, “twenty to five-and-twenty years ago, when alcohol-giving was so rampant that it was difficult to see a patient who had been a few hours at the hospital before the time of one’s visit, who had not been already put, almost as a matter of course, by the physicians or clinical assistant, on three or four ounces of brandy, or on double that amount of wine….’ This particular doctor did not give way to ‘that alcohol craze’ but because of this was considered to be the ‘most unorthodox of teachers, if not something worse than that.’ The practice was so commonplace that a doctor working in any other way was seen as very unconventional.

As opinions changed and the moral aspects of administering alcohol were highlighted, one establishment that was actively trying to dispense with the use of alcohol as a medical treatment, was the London Temperance Hospital. An article from the July 1883 British Women’s Temperance Journal records that ‘In the Temperance Hospital alcohol was not made of use of at all. The experiment carried on there was consequently of a very drastic nature – that of virtually dispensing with alcohol altogether.’

An article ‘A Sketch of the London Temperance Hospital’ in the BWTJ of September 1884 tells us that the London Temperance Hospital commenced work in Gower Street, Bloomsbury in October 1873. It was under the control of a board of teetotalers wanting to remove alcohol from medical practice. Founded on temperance principles, the use of alcohol was strongly discouraged although not totally banned.

The hospital moved to purpose built premises on Hampstead Road, near Euston and in ‘March 1881, the opening of a portion of the building took place.’ The Hospital was extended over the years including the addition of a children’s ward and a name change in 1932 to the National Temperance Hospital.

The 1884 article tells us that with another wing being added, it would provide accommodation for 120 beds and the annual hospital report documents 513 in-patients and 3,333 out-patients for the year ending April 1884. It also confirms that patients were both abstainers and non-abstainers and ‘that any who are suffering may be admitted within its portals’; there was no discrimination on this basis for admittance.

The writer of the article highlighted the increase in patient numbers for the year which ‘unmistakably proclaim the increasing value put upon the treatment here practised….’ and that the ‘successful treatment of disease without recourse to alcohol is a subject of such vast importance, that every true lover of his race can but watch with deep interest the gratifying results of the work of the London Temperance Hospital. The women of the BWTA as temperance campaigners, would have been keen to learn about positive outcomes from the hospital and to share this news with members through their publications. A BWTJ article regarding the Hospital Report for the year ending 30th April 1885, states that ‘In no case has any alcoholic medication been given.’

By the 1920’s the BWTA’s monthly periodical was called The White Ribbon, and an article provides us with a clear picture of the huge increase of in-patient numbers from the earlier years of the hospital, to 1,279 and 27,566 out-patients for the year 1920. It also records that during the 36 years of the hospital’s existence, there had only been 85 cases out of a total 29,817 in-patients, where alcohol had been administered.

The British Women’s Temperance Association – Raising Funds

The BWTA Annual Report of 1925 records a ‘circular letter sent out by the Temperance Hospital, announcing that a special effort is being made by the branches of the BWTA to raise £5000 and name a ward….’. This was a huge amount of money to raise, equivalent to over £300,000 today. The Executive Committee pointed out that while the members of the branches (which were spread across the country) were free to do what they wanted to support the hospital, the National Association could not take responsibility for raising this amount of money. Later reports confirm that funds raised for the hospital eventually reached over £4300 over eight years. I have not been able to confirm if a ward was ever named per the original letter.

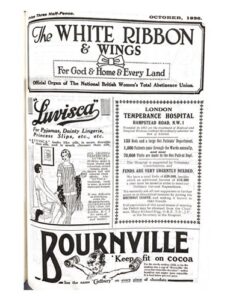

By 1926 the ‘Official Organ’ of the Association (now re-named as the National British Women’s Total Abstinence Union – NBWTAU) was called ‘The White Ribbon and Wings’. The October 1926 edition of the monthly magazine carried a front page advertisement for the London Temperance Hospital, as funds were urgently needed. The advert states that the hospital was supported by voluntary contributions and that they had a debt of £29,000, equivalent to over 1.7 million today. They also needed to raise the equivalent of over £600,000 to meet their expenditure costs.

NBWTAU Deputation to the London Temperance Hospital Board

The NBWTAU Annual Report of 1929 records that questions were being raised about the status of the Hospital by the National Executive Committee, following enquiries received from Branches who were giving financial help to the Hospital. They wanted to know the answers to the following questions –

- What proportion of the Board of Management were total abstainers?

- What proportion of the Surgical and Medical Staff were total abstainers?

- Were the Matron and Nursing Staff total abstainers?

It was agreed that a Deputation from the NBWTAU consisting of six members, would be received by the Board of the Hospital on 6th February 1929. Prior to this a letter had been received at the Association stating that as a result of a Conference between the Board of Management at the Hospital and the Medical Committee, ‘it has been agreed to restrict the forms of Alcohol used, to SVG (Brandy) and SVR (Rectified Spirits of Wine).

The White Ribbon and Wings July 1929 edition carried the report of the Deputation of the NBWTAU meeting with the Board of the Hospital.

The Deputation were keen to clarify ‘whether the Hospital was maintaining its old traditions of treating patients without alcohol, or, where it was prescribed, was it administered as Brandy or Rectified Spirit only?’. One member called attention to the 1927 Report of the Hospital, where ‘Iced Champagne and Port Wine had been given.’ It is recorded that following dissatisfaction by the Hospital Board about this action and a meeting with Medical Staff, agreement was made only for Rectified Spirits of Wine or Brandy to be given.

Confirmation was provided by the Hospital Board that of the 10 visiting medical staff, half were total abstainers and all 3 resident medical staff were total abstainers. There was, however, no obligation for any of the medical staff to be abstainers, but if two applicants having equal qualifications were before the board for appointment, then the abstainer would be given preference.

Clarity was provided by the Matron in regard to nursing staff, that no Probationers were taken on unless they were total abstainers, with this question specifically being asked on the application form. However, it wasn’t a specific requirement for Sisters and Nurses, because the opinion was held that it may decrease the chance of employing ‘suitable and capable women’.

The women of the Deputation arrived at the meeting thoroughly prepared and informed of the Hospital Reports and were not deterred from seeking answers to their questions, even when faced with the Board which was headed up the Chairman, Major Richard Rigg. They picked up on discrepancies in past Reports when no entry of medical signatures had been made when alcohol had been administered. These signatures were acknowledged by the Board as an omission on the reports but were to be found in a record called the Exceptional Cases Book.

The Deputation also produced statistical reports showing an increase in the rate of cases on alcohol from three per thousand during the first thirty three years of work at the hospital, to over four per thousand in 1928. Figures quoted for the hospital stated that ‘In 53 years this institution treated 49,000 in-patients: of these 47,000 were cured or relieved, and in only 188 cases was alcohol prescribed – less than four cases per 1000. Compared with the prevailing hospital experience, this ‘dry’ infirmary has had the highest recovery rate and the lowest death rate.

Finally, the Board expressed the desire for a representative of the NBWTAU to sit on the Hospital Board, but the NBWTAU Annual Report of 1929 records that after a ‘….very full discussion. It was agreed that the offer of a seat on the Board be not accepted….’. The concerns raised by the women of the NBWTAU deputation were not alleviated as demonstrated by their declining the offer of a seat on the Hospital Board. The White Ribbon and Wings article goes on to quote a letter received from the Chairman of the Hospital Board. The letter states that following the meeting ‘The Board deeply regret that the position reached was not to your approval. They hoped some criticism had been answered to your satisfaction.’ It would appear that the NBWTAU were adhering firmly to the ‘total abstinence’ principles of the Association.

Even though the NBWTAU eventually declined a seat on the Hospital Board, members of the Association had supported the Hospital. The funds raised by the NBWTAU in support of the hospitals invaluable work treating patients without the use of alcohol (in most cases), were the equivalent of over £250,000 today. The work of the London Temperance Hospital was quoted by Dr Courtenay C Weeks at the time as being ‘Perhaps the greatest factor which has contributed to the gradual elimination of alcohol from medical prescription in hospitals…’. Weeks states that 95 patients out of 100 were placed on daily rations of wines, spirits, or beer at a time when the Temperance Hospital was opened in 1873, but the Temperance Hospital challenged this type of treatment ‘….as not only not helpful, but definitely harmful.’ The challenge appears to have been a very successful one.

The hospital continued through changes, until it’s closure as a hospital in 1990. The buildings were then utilised for other clinics and offices until it lay derelict before demolition began in 2017 due to the High Speed Rail 2 (HS2) project.